- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

|

Sony Movie Channel will be showing a Godzilla double feature, which will be featuring Godzilla Vs. Mothra (1992) and Godzilla 2000 (1999) both english dubbed prints, times below.

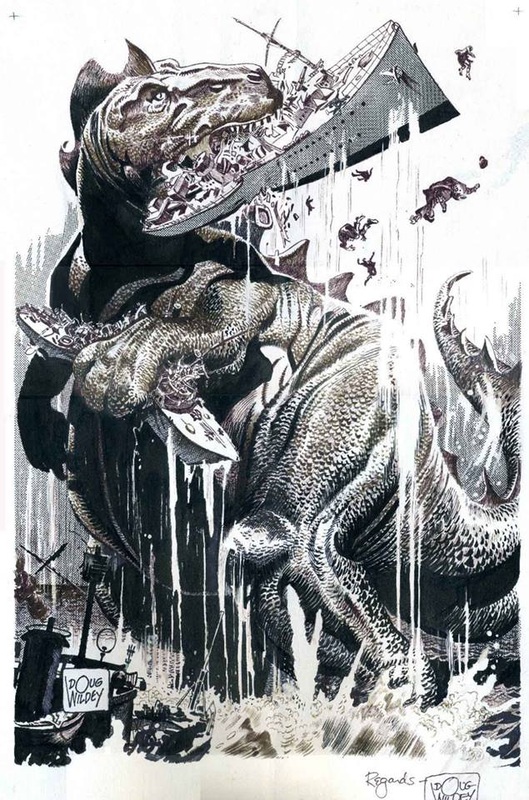

Godzilla Vs.Mothra Monday, June 2 10.00 pm E | 7.00 pm P Monday, June 2 1.30 am E | 10.30 pm P Saturday, June 7 1.10 pm E | 10.10 am P Monday, June 9 5.00 pm E | 2.00 pm P Sunday, June 22 7.30 am E | 4.30 am P Monday, June 30 10.35 am E | 7.35 am P Godzilla 2000 Monday, June 2 11.45 pm E | 8.45 pm P Monday, June 2 3.15 am E | 12.15 am P Saturday, June 7 2.55 pm E | 11.55 am P Monday, June 9 6.45 pm E | 3.45 pm P Saturday, June 21 5.50 am E | 2.50 am P Monday, June 30 8.50 am E | 5.50 am P  From The Japan Times “Godzilla” was the first Japanese movie I saw. It was also the first for many other American baby boomers, though we did not view Ishiro Honda’s 1954 original, but a version that had been heavily edited and dubbed for the U.S. market, with additional footage featuring Raymond Burr as an intrepid American reporter in Tokyo. This version was released in the U.S. in 1956 as “Godzilla, King of the Monsters!” and it became a big hit, opening the floodgates for other Japanese films starring various kaijū (giant monsters). A little over a year later, this Americanized version was then imported back to Japan as “Kaiju o Gojira” (literally, “Monster King Godzilla”) and was received enthusiastically by local fans. Since 1954, the”King of the Monsters” has appeared in 28 Toho films (and two big-budget Hollywood films, including Gareth Edwards’ new one, which opens in Tokyo on July 25), but has the old thrill gone? Though crude by today’s CGI standards, the original Godzilla has retained his primitive power — he represents powerful forces, from the natural to the manmade, that humans struggle to control or understand. In the 1954 film, the only effective weapon against Godzilla is the Oxygen Destroyer — itself so fearsome (it transforms living creatures into lifeless skeletons in seconds) that Dr. Serizawa, its conflicted creator, finally burns his research papers and ends his own life. He tries to put the dangerous genie back into the bottle, something the inventors and users of the atomic bomb knew was impossible. I saw “Godzilla, King of the Monsters!” on television sometime during the late 1950′s and, though its anti-nuclear message flew over my 9-year-old head (as was intended by the U.S. producers, who had excised most of it from the film), it left a huge impression on me. Instead of beating my chest like King Kong, the other influential creature of my childhood, I took to terrorizing the ant colonies around our house with Godzilla-like stomps. I wanted to be Godzilla, with all that destructive power at my command and the license to use it anyway I wanted, smashing Tokyo for the sheer naughty thrill of it. Or at least that’s the way it seemed to me then. Seeing the original again recently as a digitally remastered version (that Toho will release locally on June 7), I found a film which was serious and sad — utterly unlike the cheesy, campy reputation the series acquired in its other Toho entries. (The last, Ryuhei Kitamura’s “Godzilla: Final Wars,” was released to a lukewarm box office reception in 2004.) As has often been noted, “Godzilla” references the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with its stark scenes of destroyed cityscapes and radiated victims, as well as the tragic March 1954 encounter of a Japanese fishing boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon 5), with fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test on Bikini Atoll. In the film, the radiation that sickens the sailors comes not from a bomb but a nuclear-radiated monster: Godzilla. Though it’s obvious from the beginning that Godzilla is a stand-in for nuclear destruction, to a Japanese audience in ’54 — with World War II ending less than a decade earlier — his epic tromps through Tokyo, leaving flaming ruins in his path, would have reminded many of the fire-bombings unleashed by allied warplanes on major cities throughout the country. And older viewers may have associated his ground-rattling stomps with the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that leveled much of Japan’s capital and caused an estimated 142,800 deaths. That is, as a metaphor, Godzilla is somewhat mixed, but not one to be treated lightly, as every note of Akira Ifukube’s famous slashing score makes clear. What is also apparent from the new, meticulously restored version, is that, far from being a B-grade cheapie, “Godzilla” was intended as a head-to-head challenge by Toho to Hollywood’s science fiction films, then popular with young fans. At the time, Toho was one of Japan’s leading studios in terms of talent (director Ishiro Honda’s mentor and friend Akira Kurosawa was on the payroll) and resources — both financial and technical. At the same time, Toho effects wizard Eiji Tsuburaya and his staff did not have the sort of lengthy production schedule accorded to the makers of the 1953 Warner Brothers hit “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,” which was a “Godzilla” inspiration that featured a stop-motion dinosaur awakened from its 100-million-year sleep by atomic explosions. Their solution — an actor in a Godzilla suit, trashing miniature cityscapes — became a series signature, if one that grew dated over the decades, as CGI technology made its relentless advance. Nonetheless, Toho effects technicians made doing more with less a sophisticated craft. “The work that went into making Godzilla films astounded me,” comments Norman England, a lifelong Godzilla fan who worked on the six Godzilla films of the so-called Heisei era series, which streched from 1999 to 2004. “You’d have dozens of people laboring for days on end just to make one brief shot of Godzilla’s foot smashing into a country hotel,” says England. Also, though big, scaly and fire-breathing, the first Godzilla looks little like his latter incarnations, which have ranged from the grotesquely cute (including Godzilla’s bumpy-headed son, Minilla) to the atomically glowing and ferocious. “A new suit is built for almost every film, with each somewhat different from the last.” England notes — which makes snarky fan nit-picking over the look of the title monster in Gareth Edwards’ new “Godzilla” seem beside the point. Yes, he’s bigger and bulkier than the original, but so are many latter Toho Godzillas. That is, he’s squarely within the series’ hypertrophied tradition, in contrast to the iguana-like beast in Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Godzilla film — an aberration rightly derided by Japanese fans. Despite Dr. Serizawa’s sacrificial suicide in the original 1954 version, Godzilla returns in film after film, sometimes as humankind’s enemy and sometimes, as in the latest Hollywood iteration, its unlikely protector. England says that diversity is the character’s strength: “Godzilla has been everything: nuclear metaphor, the hero of humanity and even a parent.” Toho is set to release a digitally remastered version of the original, viewable now as close to its pristine 1954 condition as 2014 technology can make it. The Gareth Edwards version may be the franchise’s biggest box-office monster ever — it earned nearly $200 million worldwide in its first weekend — but if you don’t know the first film, you don’t know Godzilla. And not, please, the one with Raymond Burr. For the first time ever on vinyl the full score to the legendary monster movie that started it all GODZILLA by AKIRA IFUKUBE

Death Waltz Recording Company are proud to be unearthing the legendary monster of our time and bringing him to vinyl in the shape of Akira Ifukube’s score to GODZILLA. Starkly different to the usual view of The Big G as the ultimate monster wrestler, Ifukube’s music is intense, dark, and reflects Ishiro Honda’s film as a pure horror film. While the score opens with the jaunty riff that would eventually become Godzilla’s Theme, the majority of the music alternates between pounding brass and mournful strings as we witness the death and destruction that comes in Godzilla’s wake. Ifukube uses low string notes as a sinister motif to herald the arrival of the creature, and then turns up the brass to eleven, creating an atmosphere of pure apocalypse. More horrifying still are the piercing strings that score the oxygen destroyer, the device that would destroy Godzilla. Big laments are used as the characters question the use of the machine as a weapon of mass destruction, and it’s this remarkable human quality that infuses the score with its unique feel. Help us celebrate the sixtieth birthday of the greatest monster to walk the earth, and the powerhouse musical experience that is Akira Ifukube’s GODZILLA. DELUXE GATEFOLD EDITION LTD TO 400 WORLDWIDE (£22.00) 180g Atomic Breath vinyl, housed in a heavyweight tip-on, case-bound gatefold jacket printed on beautiful textured Galtex Prima card containing an exclusive full colour booklet with liner notes by Japanse cinema expert Jasper Sharpe & Film On Wax Editor Charlie Bridgen , with exclusive art by Cheung Chung Tat wrapped in an OBI strip. STANDARD EDITION LTD TO 400 WORLDWIDE (£17.00) 180g Green vinyl housed inside a 350gsm single pocket jacket with a poster. Check out Death Waltz's site here (Note: These are not available in the US.) TRACKLISTING SIDE 1 Godzilla Approaches Godzilla Main Title Medley/ Ship Music / Sinking Of Eikou – Maru Sinking Of Bingou Maru Anxieties On Ootojima Island Ootojima Temple Festival Stormy Ootojima Island Theme For Ootojima Island Japanese Army March I Horror Of The Water Tank Godzilla Comes Ashore SIDE 2 Godzilla’s Rampage Desperate Broadcast Godzilla Comes To Tokyo Bay Intercept Godzilla Tragic Sight Of The Imperial Capital Oxygen Destroyer Prayer For Peace Japanese Army March II Godzilla At The Ocean Floor Ending Secret Hidden Track Also check out Empire Magazine to listen to the full soundtrack here.  From NPR.org There have been hundreds of monster movies over the years, but only a handful of enduringly great movie monsters. Of those, only two were created for the screen: King Kong, the giant ape atop the Empire State Building, and his Japanese heir, Godzilla, the city-flattening sea monster who's a genuinely terrific pop icon. He not only stars in movies — Hollywood is bringing out a new Godzilla on May 16 — but he's even played basketball with Charles Barkley in a commercial for Nike. It's been six decades since Godzilla first hit the screen, and to celebrate the big guy's birthday, Rialto Pictures is releasing Ishiro Honda's 1954 original — in a restored, 60th-anniversary edition — in theaters. I've seen Godzilla many times since I was a kid, but watching it again, I was struck that it might be the best single film about the terrors of the nuclear age. I suspect you know the plot. It begins when American H-bomb tests in the Pacific disturb the watery environment that's the home of Gojira, as the monster is called in Japanese. After sinking assorted ships, this enormous beast winds up in Tokyo, where he stomps on buildings, flosses with power lines and blasts citizens with his radioactive bad breath. When the army is unable to stop him, the only hope is a new invention called the Oxygen Destroyer. But its idealistic creator is reluctant to reveal it for fear it will become a weapon — just look at the destruction that followed from splitting the atom. Yet even as the inventor says this, the movie itself is offering us the seductive spectacle of violent ruin. And make no mistake: Destruction is great to look at. There's an amoral pleasure to be had in watching Godzilla reduce Tokyo to fiery rubble, rather like the beauty of seeing those napalmed palm trees flare like matches in Apocalypse Now or the illicit thrill of seeing the White House get obliterated in Independence Day — before Sept. 11, of course. Quite clearly, it's this joy in destruction that helped make Godzilla influential, especially in Hollywood, which over the past half-century has fed the worldwide audience's appetite for images of spectacular violence. That said, Godzilla's real strength lies not in its effects — impressive for the time — but in its underlying emotional and cultural seriousness. It's not simply that the music is often doleful rather than exciting or that we see doomed children set off Geiger counters. The movie has a gravity that comes from being created in a Japan that knew what it was to have children die from radiation poisoning and to see its capital city in flames. Both drawn to and terrified of the monster's power, the movie is steeped in Japan's traumatic historical experience. It has weight. It means something. Godzilla's resonance is also inseparable from something else that once defined the best monster movies — a sense of compassion for the monster. Boris Karloff's Frankenstein may have been scary, but we also felt his frailty and fear at being hunted. King Kong was dangerous, sure, but his eyes were charged with almost human feeling when he gazed at Fay Wray. The same is true of Godzilla, who starts out wreaking havoc but, by the film's end, takes on a melancholy, sad-faced grandeur. These days, our pop culture doesn't encourage such identification. Ever since Jaws and Alien and Predator, whose creatures are ruthless murder machines, our monsters have increasingly become soulless things to be destroyed. Consider today's favorite monster, the zombie. Although zombies could hardly seem more human — heck, they just were human — the walking dead have no individuality and run in packs. They basically exist to have their heads shot off in movies and TV shows that resemble video games. Godzilla is not remotely like this. In Jim Shepard's wonderful short story "Gojira, King of the Monsters" — part of his collection titled You Think That's Bad — Shepard offers a fictionalized account of the making of the movie. At one point, Shepard has director Ishiro Honda explain why the vanquishing of Godzilla feels so sad, and his words sum up brilliantly what gives Godzilla its strange power. "By the time the movie ends," Honda says, "[Godzilla] is like a hero whose departure we regret. It's like part of us leaving. That's what makes it so hard. The monster the child knows best is the monster he feels himself to be." |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

© 2011-2024 Kaiju Battle. All Rights Reserved.

|

Visit Our Social Media Sites

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed