- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

|

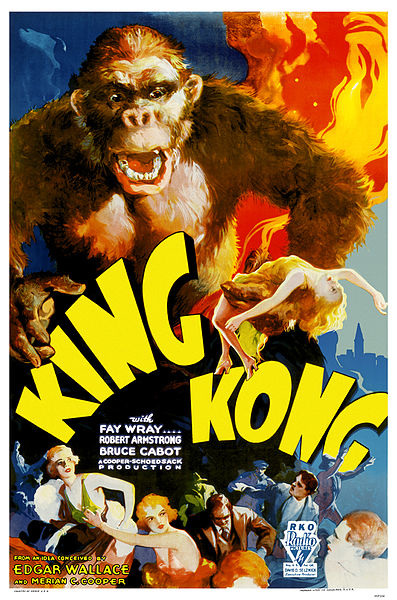

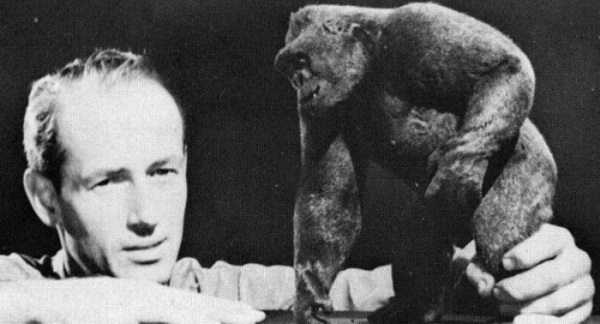

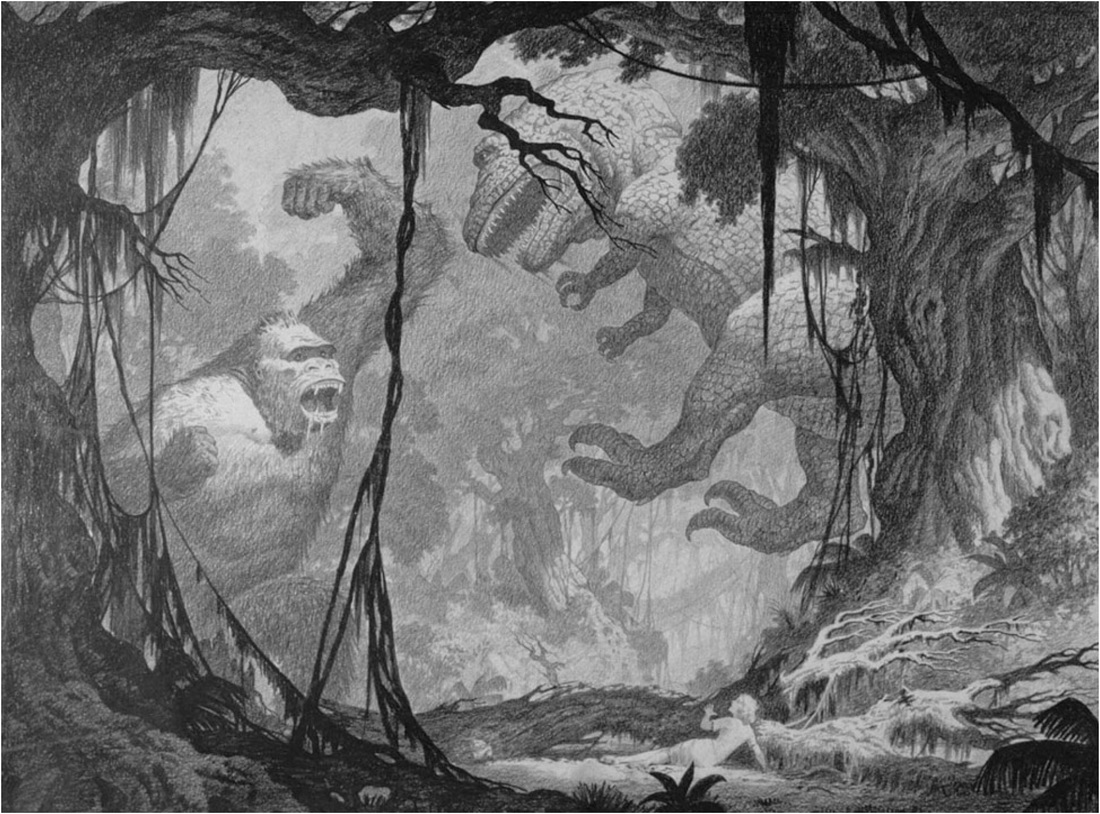

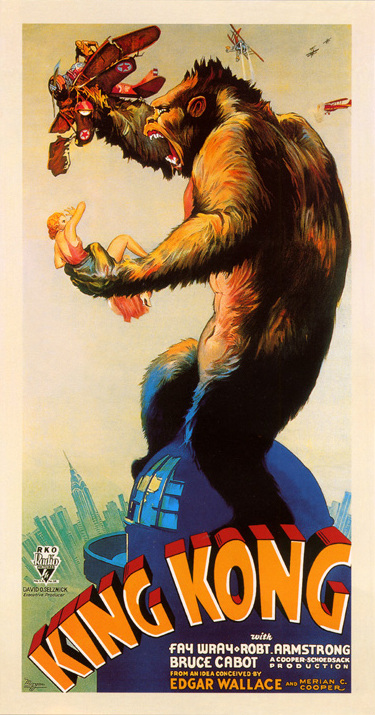

In a few months we get a brand new King Kong film Kong: Skull Island, and from what we have seen this looks to be an awesome movie with a Kong like none before. But in the beginning of the 1930's there truly was no Kong, only an idea conceived by Merian C. Cooper. To create Kong involved a lot of work and time, more then some may realize, today most effects are done with computers, obviously not back then. To create Kong and his world involved processes like stop-motion animation, matte painting, rear projection, and miniatures, all groundbreaking special effects at the time. Many of the prehistoric creatures inhabiting Skull Island, as well as Kong, were brought to life through the use of stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien and his assistant, Buzz Dixon. Models of the creatures needed to be made, for Kong Marcel Delgado constructed Kong from designs and directions from Cooper and O'Brien on a one-inch-equals-one-foot scale to simulate a creature 18 feet tall. Four models were built; two jointed 18-inch aluminum, foam rubber, latex, and rabbit fur models (to be rotated during filming), one jointed 24-inch model of the same materials for the New York scenes, and a small model made of lead and fur for the the fall from the Empire State Building. His lips, eyebrows, and nose were fashioned of rubber, his eyes of glass, and his facial expressions controlled by thin, bendable wires threaded through holes drilled in his aluminum skull. Kong's skin had to be replaced often due to the hot studio lights drying out the rubber and they had to completely rebuild his facial features because of this as well. The scenes were grueling to shoot because the special effects crew realized that they couldn’t stop, because it would make the movements of the creatures seem inconsistent and the lighting wouldn’t have the same intensity over the many days it took to fully animate a finished sequence. A device called the surface gauge was used in order to keep track of the stop-motion animation performance. The iconic fight between Kong and the T-Rex alone took a staggering seven weeks to be completed. For close-up shots a huge bust of Kong was used made of wood, cloth, rubber, and bearskin by Delgado, E. B. Gibson, and Fred Reefe. Inside the structure, metal levers, hinges, and an air compressor were operated by three men to control the mouth and facial expressions. Its fangs were 10 inches in length and its eyeballs 12 inches in diameter. One issue with the bust was scale, it didn't match the smaller models and would have been between 30 to 40 feet tall for the full body, nearly twice the size. There was also arms and a leg. While both arms were right arms one was articulated the other not, the articulated arm was used in many scenes where Kong grabs Ann. The non articulated leg was used in scenes where Kong stepped on victims. Many of the dinosaurs were constructed in the same way as Kong and based on Charles R. Knight's murals in the American Museum of Natural History. Materials used were cotton, foam rubber, latex sheeting, and liquid latex, and football bladders were placed inside some models to simulate breathing. A scale of one-inch-equals-one-foot was employed with these as well and models ranged from 18 inches to 3 feet in length. Several of the models were originally built for Creation (a film about a group of travelers shipwrecked on an island of dinosaurs) and sometimes two or three models were built of individual species. John Cerasoli carved wooden duplicates of each model, as stand-ins for test shoots, because the studio lights would dry out the latex skin.  Matte painting was use on the film for a number of backdrops, the scene when the Venture crew first arrive was painted in glass by matte painters Henry Hillinck, Mario Larrinaga and Byron C. Crabbé, and the background of the scenes in the jungle (a miniature set) were also painted in glass to convey the illusion of deep and dense jungle foliage. The most difficult achievement for the film makers was to accomplish how to make live-action footage interact with stop-motion animation in order to make the interaction between the humans and the creatures of the island work and seem believable. Due to limited technology at the time the composite shots were achieved in-camera, the most simple of these effects were accomplished by exposing part of the frame, than running the same piece of the film through the camera again by exposing the other part of the frame with a different image. Two processes were used the Dunning process (a process of loading two reels of film into a camera, so that they both pass through the camera gate together (bipacking)) and the Williams process (uses an optical printer, the first such device that synchronized a projector with a camera, so that several strips of film could be combined into a single composited image), in order to produce the effect of a traveling matte. The Dunning process was used in the climactic scene where one of the Curtiss Helldiver planes attacking Kong crashes from the top of the Empire State Building, and in the scene where natives are running through the foreground, while Kong is fighting other natives at the wall, the Williams process for the scene where Kong is shaking the sailors off the log, as well as the scene where Kong pushes the gates open. The Williams process was more versatile because the special effects crew could film the foreground, the stop-motion animation, the live-action footage, and the background, and combine all of those elements into one single shot. This process would continue to be used for films until the late 1980's. Rear projection was other technique used on the film the actor would have a translucent screen behind him where a projector would project footage onto the back of the translucent screen. It was used for the scene where Kong and the T-Rex fight while Ann watches from the branches of a nearby tree. The stop-motion animation was filmed first. Fay Wray then spent a twenty-two hour period sitting in a fake tree acting out her observation of the battle, which was projected onto the translucent screen while the camera filmed her witnessing the projected stop-motion battle. It was also used for the scene where sailors from the Venture kill a Stegosaurus. Rear projection was use along with miniatures, a tiny screen was built into the miniature set onto which live-action footage would then be projected. A fan pumped cool air to prevent the footage that was projected from melting or catching fire. This miniature rear projection was also used in the scene where Kong is trying to grab Driscoll, who is hiding in a cave. The scene where Kong puts Ann in the top of a tree switched from a puppet in Kong's hand to a projected footage of Ann sitting.

The hardest scene to shoot because all of the elements in the sequence had to work together at the same time, was the scene where Kong fights the snake-like dinosaur in his lair. The scene was accomplished through the use of a miniature set, stop-motion animation for Kong, background matte paintings, real water, foreground rocks with bubbling mud, smoke and two miniature rear screen projections of Driscoll and Ann. Overall filming took eight months mostly because of the special effects process, many of these techniques were used for years to come in other famous films like Star Wars, Raiders Of The Lost Ark, RoboCop, and many more including even Toho's Godzilla. Even films made today will incorporate some of these techniques still. Note: much of the information here comes from Wikipedia.

0 Comments

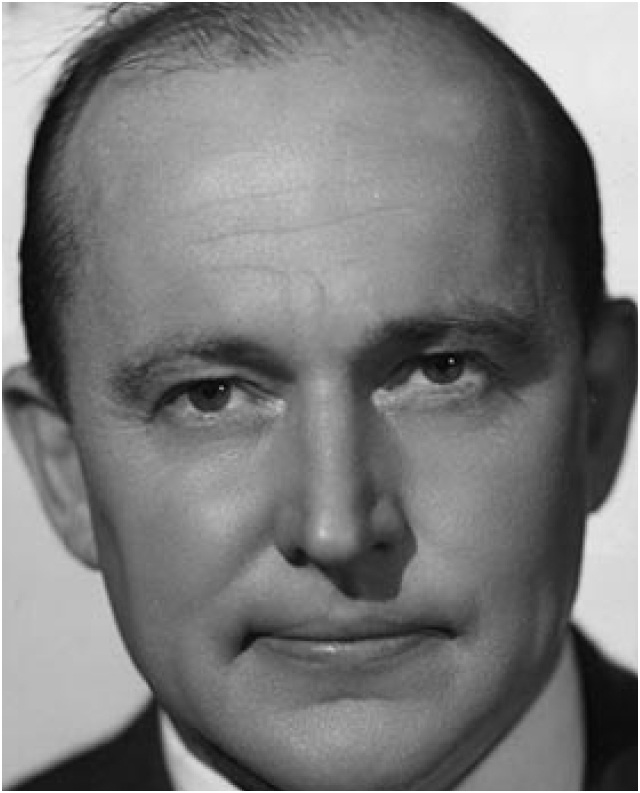

On the latter point, a sea voyage in 1922 on the Wisdom II, a ship whose goal was to seek out adventure and document it in print and film, would carry Cooper and his fellow seafarers to places where head hunters appeased angry spirits with human sacrifices, to an African kingdom ruled by the reputed descendant of King Solomon, to a jungle-covered plateau isolated by smoldering volcanoes, and to encounters with stormy seas and cut-throat pirates. But it was on one remote island during the wanderings of the Wisdom that Cooper and a landing party discovered hundreds of gigantic lizard creatures, a real-life encounter with a primordial lost world which would grow in his imagination into the giant gorilla Kong and the prehistoric creatures populating Skull Island. The character of Carl Denham, the movie producer in King Kong who leads the Venture on the film-making expedition to Skull Island, was largely patterned after Cooper himself. In the film’s opening, a night watchman where the Ventureis docked says of Denham: “They say he ain’t scared of nuthin.’ If he wants a picture of a lion he goes up to him and tells him to look pleasant!” Such was Cooper who, with Ernest Schoedsack, had plunged into the jungles of Siam where man-eating tigers prowled to capture some hardy specimens for their adventure story Chang, the 1927 release that would actually become famed for the stampeding herd of wild elephants Cooper and Schoedsack orchestrated for their film. Before Chang had been the adventure of Grass, a 1925 release and one of the pioneering documentary films that saw Cooper, Schoedsack, and an heiress and former spy named Marguerite Harrison join the nomadic Bakhtiari tribe on an arduous seasonal journey across a raging icy river and over a towering, ice-capped mountain range to a distant, verdant land. A trilogy of Cooper-Schoedsack movie expeditions was capped by the 1929 fictional drama The Four Feathers, a swash-buckling adaptation of the A.E.W. Mason novel that included location shooting in Africa that was duplicated on California sets—the first time a far-flung location was so matched by Hollywood illusionists. What else did Merian Cooper bring to Kong? Before the movie expeditions and Wisdom voyage was the hard school of war. In World War I, Cooper was one of the pioneer warriors of the air, flying the infamous De-Haviland 4 planes that earned the dubious nickname “flaming coffins.” In one raging dogfight, Cooper was shot down in flames but survived through his steady nerve and skill as a pilot. After recovering while a German prisoner-of-war, Cooper was charged with leading American humanitarian missions in Poland before he left to help form the Kosciuszko Squadron, a group of all-American, battle-hardened pilots who thirsted for adventure and the cause of fighting the Bolsheviks who were invading Poland. After flying dozens of dangerous combat raids, Cooper’s luck ran out and he was again shot down and captured by the enemy. Only an assumed name prevented his being executed outright—as a leader of the Kosciuszko Squadron he had a price on his head. Cooper endured hellish months in Soviet prison camps, surviving through his own steely will and the help of his later movie partner, Marguerite Harrison. Finally, fearing his imminent execution, Cooper made a great escape with two Polish prisoners to the barbed-wire frontier border of Latvia and freedom. Back home, where he settled in New York, Cooper’s love of flying eventually led him to become a pioneering executive in the nascent field of commercial aviation, including being an elected director of Pan-American Airways. In addition to being a major player among New York’s business elite, Cooper became a confidant of movie producer David O. Selznick. In 1931, when Selznick became executive vice-president in charge of production at RKO, he invited Cooper to join him and installed Cooper as one of his trusted executive assistants. It was there that Cooper had the power and the backing to make the film which had become his obsession, the story he had been fleshing out since the late 1920s while a restless New York business executive whose memories of adventure were taking the form of the ultimate movie expedition.

In 1991, King Kong was awarded preservation priority status as one of 25 classic movies added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry and in 1998 King Kong was named one of the top 100 American films by the American Film Institute (#43 on the list). That Kong endures is a testament to the vision of Merian Cooper who in a magical act of motion picture alchemy combined his wildest imagining with the memories of true-life adventure, leaving the world a great legacy of the imagination.

Article from the Kong Of Skull Island website by Mark Cotta Vaz. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

|

© 2011-2024 Kaiju Battle. All Rights Reserved.

|

Visit Our Social Media Sites

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed