- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

|

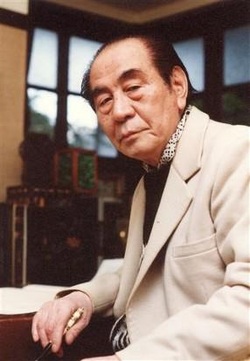

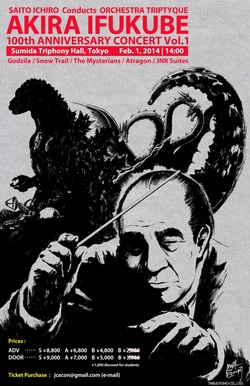

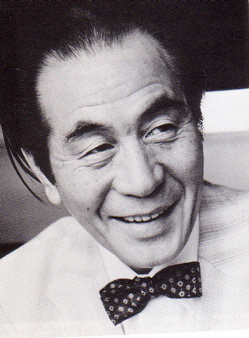

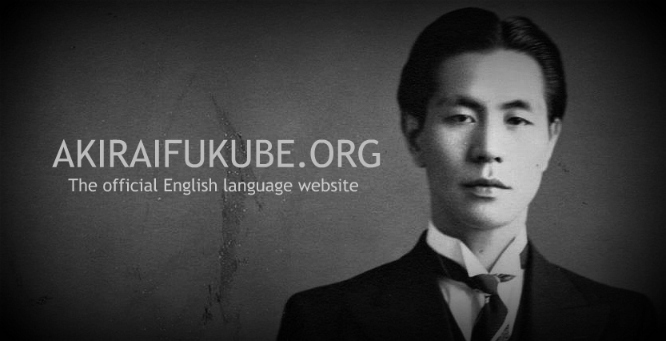

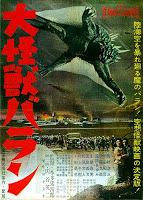

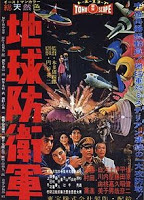

Akira Ifukube (伊福部 昭 Ifukube Akira, 31 May 1914 – 8 February 2006) was a Japanese composer of classical music and film scores, perhaps best known for his work on the soundtracks of the Godzilla movies by Toho. Biography Akira Ifukube was born on May 31, 1914 in Kushiro on the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, the third son of a Shinto priest. Much of his childhood was spent in areas with a mixed Japanese and Ainu population, and his father, unusually for the time, socialised with Ainu. Ifukube was strongly influenced by the traditional music of both peoples, and studied the violin and the shamisen. His first encounter with classical music occurred when attending secondary school in Hokkaidō's capital, Sapporo. Legend has it that Ifukube decided to become a composer at the age of 14 after hearing a radio performance of Igor Stravinsky's ballet, The Rite of Spring. He also cited the music of Manuel de Falla as a major influence. Ifukube went on to study forestry at Hokkaido University and composing in his spare time, which prefigured a line of self-taught Japanese composers such as Tōru Takemitsu and Takashi Yoshimatsu. His first piece was the piano solo, Piano Suite (later the title was changed to Japan Suite, arranged for orchestra). This piece was dedicated to the pianist George Copeland who was then living in Spain. Atsushi Miura, musicologist and Ifukube's friend in university, sent a fan letter to Copeland. Copeland replied, "It is wonderful that you listen my disc in spite of you living in Japan, the opposite side of the earth. I imagine you may compose music. Send me some piano pieces." Then Miura, who was not a composer, presented Ifukube and this piece to Copeland. Copeland promised to interpret it, but the correspondence was unfortunately stopped because of the Spanish Civil War. Ifukube's big break came in 1935, when his first orchestral piece, Japanese Rhapsody, won the first prize in an international contest for young composers promoted by Alexander Tcherepnin. The judges of that contest—Albert Roussel, Jacques Ibert, Arthur Honegger, Alexandre Tansman, Tibor Harsányi, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, and Henri Gil-Marchex—were unanimous in their selection of Ifukube as the winner. The next year, Ifukube studied modern Western composition while Tcherepnin was visiting Japan, and in 1938 his Piano Suite obtained an honourable mention at the I.C.S.M. festival in Venice. In the late 1930s his music, especially Japanese Rhapsody, was performed in Europe on a number of occasions. On completing University, he worked as a forestry officer and lumber processor, and towards the end of the Second World War was appointed by the Japanese Imperial Army to study the elasticity and vibratory strength of wood. He suffered radiation exposure after carrying out x-rays without protection, a consequence of the wartime lead shortage. Thus, he had to abandon forestry work and became a professional composer and teacher. Ifukube spent some time in hospital due to the radiation exposure, and was startled one day to hear one of his own marches being played over the radio when General Douglas MacArthur arrived to formalize the Japanese surrender. From 1946 to 1953, he taught at the Nihon University College of Art, during which period he composed his first film score for The End of the Silver Mountains, released in 1947. Over the next fifty years, he would compose more than 250 film scores, the high point of which was his 1954 music for Ishirō Honda's Toho movie, Godzilla. Ifukube also created Godzilla's trademark roar – produced by rubbing a resin-covered leather glove along the loosened strings of a double bass – and its footsteps, created by striking an amplifier box. Despite his financial success as a film composer, Ifukube's first love had always been his general classical work as a composer. In fact his compositions for the two genres cross-fertilized each other. For example, he was to recycle his 1953 music for the ballet Shaka, about how the young Siddhartha Gautama eventually became the Buddha, for Kenji Misumi's 1961 film Buddha. Then in 1988 he reworked the film music to create his three-movement symphonic ode Gotama the Buddha. Meanwhile he had returned to teaching at the Tokyo College of Music, becoming president of the college the following year, and in 1987 retired to become head of the College's ethnomusicology department. He trained younger generation composers such as Toshiro Mayuzumi, Yasushi Akutagawa and Kaoru Wada, Yssimal Motoji and Imai Satoshi. He also published Orchestration, a 1,000-page book on theory. He died in Tokyo at Meguro-ku Hospital of multiple organ dysfunction on February 8, 2006 at the age of 91. Honors The Japanese government awarded Ifukube the Order of Culture. Subsequently, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Third Class.  Selected Works Orchestral Japanese Rhapsody (1935) Triptyque aborigene for chamber orchestra (1937) Symphony Concertante for piano and orchestra (1941) Ballata sinfonica (1943) Overture to the Nation of Philippines (1944) Salome (1948) – ballet based on Oscar Wilde's play of the same name. Ifukube revised and expanded the score in 1987. The piece is written in a conservative, late-romantic style reminiscent of Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky or even Khachaturian. Drumming of Japan (1951, revised 1984) Symphonic Fantasia No. 1 (1954, revised 1983) Sinfonia Tapkaara (1954, revised 1979) Ritmica Ostinata for piano and orchestra (1961, revised 1971) Ronde in Burlesque for wind orchestra (1972, arranged to orchestra in 1983) Violin Concerto No. 2 (1978) Lauda concertata for marimba and orchestra (1979) Symphonic Fantasia No. 2 (1983) Symphonic Fantasia No. 3 (1983) Gotama the Buddha, symphonic ode for mixed chorus and orchestra (1989) Japanese Suite for orchestra (1991) Japanese Suite for string orchestra (1998)  Chamber And Instrumental Piano Suite (1933) Toccata for guitar (1970) Fantasia for baroque lute (1980) Sonata for violin and piano (1985) Ballata sinfonica for duo-treble and bass 25-stringed koto (2001) Vocal Ancient Minstrelsies of Gilyak Tribes (1946) Three Lullabies among the Native Tribes on the Island of Sakhalin (1949) Eclogues after Epos among Aino Races for solo voice and 4 kettle drums (1950) A Shanty of the Shiretoko Peninsula (1960) The Sea of Okhotsk for soprano, bassoon, piano (or harp) and double bass (1988) Tomo no oto for traditional ensemble and orchestra (1990) Lake Kimtaankamuito (Lake Mashū) (摩周湖 Mashū-ko?) for soprano, viola and harp or piano (1992) La Fontaine sacrée for soprano, viola, bassoon and harp (1964, 2000); arrangement by the composer from the 1964 film score Mothra vs. Godzilla.  Film Scores Snow Trail (1947) The Quiet Duel (1949) Anatahan (アナタハン), also known as The Saga of Anatahan (1953) Godzilla (1954) Dobu (film) 1954 Ningen gyorai kaiten (1955) The Burmese Harp (1956) Rodan (1956) The Mysterians (1957) Varan the Unbelievable (1958) The Birth of Japan (1958) Battle in Outer Space (1959) The Big Boss (Boss of the Underworld) (1959) Daredevil in the Castle (1961) The Tale of Zatoichi (1962) King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) Chushingura (1962) Wanpaku Ouji no Orochi Taiji (1963) Atragon (1963) Zatoichi the Fugitive (1963) Zatoichi on the Road (1963) Fight, Zatoichi, Fight (1964) Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) Dogora (1964) Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964) Whirlwind (1964) Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965) Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965) The War of the Gargantuas (1966) Daimajin (1966) Wrath of Daimajin (1966) Return of Daimajin (1966) King Kong Escapes (1967) Zatoichi Challenged (1967) Destroy All Monsters (1968) Latitude Zero (1969) Space Amoeba (1970) Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972) Sandakan No. 8 (1974) Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975) Lady Origin (1978) Dozoku no ranjo (1991) Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991) Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992) Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (1993) Kushiro Marshland (1993) Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995) In addition, his work were also used in Godzilla vs. Biollante, Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, Godzilla 2000, Godzilla vs. Megaguirus, Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, and Godzilla: Final Wars.

0 Comments

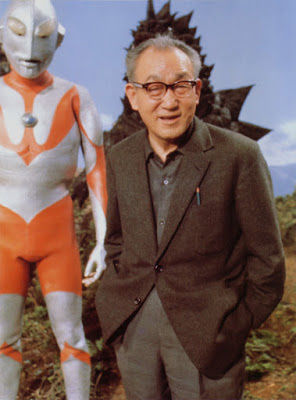

Eiji Tsuburaya (円谷 英二 Tsuburaya Eiji) (Eiichi Tsumuraya (円谷 英一 Tsumuraya Eiichi); July 7, 1901 – January 25, 1970, in Sukagawa, Fukushima) was the Japanese special effects director responsible for many Japanese science-fiction movies, including the Godzilla series. In the United States, he is also remembered as the creator of Ultraman. Early Life Tsuburaya described his childhood as filled with "mixed emotions." He was the first son of Isamu Shiraishi and Sei Tsuburaya, with a large extended family. His mother died when he was only three and his father moved to China for the family business. Young Eiji was raised by his barely older uncle, Ichiro, and his paternal grandmother, Natsu. He attended elementary school at the Sukagawa Choritsu Dai'ichi Jinjo Koutou Shogakko beginning in 1908, and two years later, he took up the hobby of building model airplanes, due to the sensational success of Japanese aviators, an interest he would retain for the rest of his life. In 1915, at the age of 14, he graduated the equivalent of High School, and begged his family to let him enroll in the Nippon Flying school at Haneda. After the school was closed on account of the accidental death of its founder, Seitaro Tamai, in 1917, Tsuburaya attended trade school. He became quite successful in the research and development department of the Utsumi toy company, but a chance meeting at a company party in 1919, set the course for his destiny—he was offered a job by director Yoshiro Edamasa, a job that would train him to be a motion picture cameraman. While the Tsuburaya family's traditional religion was Nichiren Buddhism, Tsuburaya converted to Roman Catholicism in his later years (his wife had already been a practicing Roman Catholic).  Early Career And War Propaganda In 1919, his first job in the film industry was as an assistant cinematographer at the Nippon Katsudou Shashin Kabushiki-kaisha (Nippon Cinematograph Company or Kokkatsu for short) in Kyoto, which later became better known as Nikkatsu. After serving as a member of the correspondence staff to the military from 1921 to 1923, he joined Ogasaware Productions. He was head cameraman on Hunchback of Enmeiin (Enmeiin no Semushiotoko), and served as assistant cameraman on Teinosuke Kinugasa's ground-breaking 1925 film, Kurutta Ippeiji (A Page of Madness). He joined Shochiku Kyoto Studios in 1926 and became full-time cameraman there in 1927. He began using and creating innovative filming techniques during this period, including the first use of a camera crane in Japanese film. In the 1930 film Chohichiro Matsudaira, he created a film illusion by super-imposition. Thus began the work for which he would become known—special visual effects. 1930 was also the year of his marriage to Masano Araki. Hajime, the first of their three sons, was born a year later. During the 1930s, he moved between a number of studios and became known for his meticulous work. It was during this period that he saw a film that would point towards his future career. After his international success with Godzilla in 1954, he said, "When I worked for Nikkatsu Studios, King Kong came to Kyoto and I never forgot that movie. I thought to myself, 'I will someday make a monster movie like that.'" In 1938 he became head of Special Visual Techniques at Toho Tokyo Studios, setting up an independent special effects department in 1939. He expanded his technique greatly during this period and earned several awards, but did not stay long at Toho. During the war years (the Second Sino-Japanese war and World War II) he directed a number of propaganda films and produced their special effects for Toho's Educational Film Research Division created by decree of the imperial government. Those include Kōdō Nippon (The Imperial Way of Japan) (1938), Kaigun Bakugeki-tai (Naval Bomber Squadron) (1940), The Burning Sky (Moyuru ōzora) (1940), Hawai Mare oki kaisen (The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya) (1942), Decisive Battle in the Skies (Kessen-no Ōzara-e) (1943) and Kato hayabusa sento-tai (1944). According to legend, Tsuburaya's work on The War at Sea... was so impressive that General MacArthur's film unit is said to have sold footage of the film to Frank Capra for use in Movietone newsreels as actual footage of the attack on Pearl Harbor. During the Occupation of Japan following the war, Tsuburaya's wartime association with such propaganda films proved a hindrance to his finding work for some time. He went freelance with his own production company, Tsuburaya Visual Effects Research (working on films for other studios), until he returned to Toho in the early 1950s.  Toho Years As head of Toho's Visual Effects Department (which was known as the "Special Arts Department" until 1961), that he established in 1939, he supervised around an average of sixty craftsmen, technicians and cameramen. It was here that he became part of the team, along with director Ishirō Honda and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, that created the first Godzilla film in 1954, and were dubbed by Toho's advertising department as "The Golden Trio". For his work in Godzilla (ゴジラ - Gojira), Tsuburaya won his first "Film Technique Award". In contrast to the stop motion technique most famously used Willis O'Brien to create the 1933 King Kong, Tsuburaya used a man in a rubber suit to create his giant monster effects. This technique, now most closely associated with Japanese kaiju or monster movies, has come to be called suitmation (originated in the Japanese fan press during the 1980s). Through intense lighting and high-speed filming, Tsuburaya was able to add to the realism of the effects by giving them a slightly slower, ponderous weightiness. This technique, using detailed miniatures with men-in-monster-suits, is still being used today (but combined with CGI techniques as well) and is now considered a traditional Japanese craft art. The tremendous success of Godzilla led Toho to produce a series science fiction films, films introducing new monsters, and further films involving the Godzilla character itself. The most critically and popularly successful of these films were those involving the team of Tsuburaya, Honda and Tanaka, along with the fourth member of the Godzilla team, composer Akira Ifukube. Tsuburaya continued producing the special effects for non-kaiju films like The H-Man (1958), and The Last War (1961), and won another Japanese Movie Technique Award for his work in the 1957 science-fiction film The Mysterians. He also won another award in 1959 for the creation of the "Toho Versatile System", an optical printer for widescreen pictures, which he built in-house and first used on The Three Treasures in 1959 (Tsuburaya was continually frustrated by the poor state of equipment he was forced to use, and Toho's money-pinching that prevented the acquisition of new motion picture technologies). A loyal company man, Tsuburaya continued to work at Toho Studios until his death in 1970. Tsuburaya Productions In the 1940s, Tsuburaya started his own special effects laboratory (set up at his home), and in 1963, founded his own studio for visual effects, Tsuburaya Productions. In 1966 alone, this company aired the first 'monster' series for television, Ultra Q beginning in January, followed it with the highly popular Ultraman in July, and premiered a comedy-monster series, Booska, the Friendly Beast in November. Ultraman became the first live-action Japanese television series to be exported around the world, and spawned the Ultra Series which continues to this day.

|

ArchivesCategories

All

|

|

© 2011-2024 Kaiju Battle. All Rights Reserved.

|

Visit Our Social Media Sites

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

- Home

- Features

- Movies/Media

- Collectibles

- Comics/Books

-

Databases

-

Figure Database

>

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus 30 cm Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part One

- X-Plus Large Monster Series Godzilla/Toho Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Pre-2007

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Gigantic Series

- X-Plus Daiei/Pacific Rim/Other

- X-Plus Daiei/Other Pre-2009

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part One

- X-Plus Toho/Daiei DefoReal/More Part Two

- X-Plus Godzilla/Toho Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

- Star Ace/X-Plus Classic Creatures & More

-

X-Plus Ultraman

>

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part One

- X-Plus Ultraman Pre-2012 Part Two

- X-Plus Ultraman 2012 - 2013

- X-Plus Ultraman 2014 - 2015

- X-Plus Ultraman 2016 - 2017

- X-Plus Ultraman 2018 - 2019

- X-Plus Ultraman 2020 - 2021

- X-Plus Ultraman 2022 - 2023

- X-Plus Ultraman Gigantics/DefoReals

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC

- X-Plus Ultraman RMC Plus

- X-Plus Ultraman Other Figure Lines

- X-Plus Tokusatsu

- Bandai/Tamashii >

- Banpresto

- NECA >

- Medicom Toys >

- Kaiyodo/Revoltech

- Diamond Select Toys

- Funko/Jakks/Others

- Playmates Toys

- Art Spirits

- Mezco Toyz

-

X-Plus Toho/Daiei/Other

>

- Movie Database >

- Comic/Book Database >

-

Figure Database

>

- Marketplace

- Kaiju Addicts

RSS Feed

RSS Feed